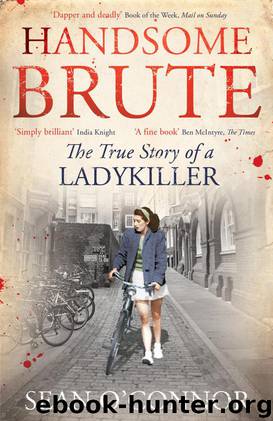

Handsome Brute: The True Story of a Ladykiller by O'Connor Sean

Author:O'Connor, Sean [O'Connor, Sean]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781471101359

Publisher: Simon & Schuster UK

Published: 2013-02-14T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Thursday 20 June 1946

[He] walked home from Moorgate Station across the ruins. Pausing at the bastion of the Wall near St Giles’s, he looked across at the horrid waste, for horrid he felt it to be; he hated mess and smashed things; the squalor of ruin sickened him; like Flaubert, he was aware of an irremediable barbarism coming up out of the earth, and of filth flung against the ivory tower. It was a symbol of loathsome things, war, destruction, savagery . . .

Rose Macaulay, The World My Wilderness, 1950

To British servicemen returning home from the war, London in 1946 presented a much-changed face; half familiar, yet wrecked, ravaged and ruined.

Throughout hostilities, the city had experienced 1,224 bomb alerts – about one every thirty-six hours. It had been raided 354 times by piloted aircraft and from 1944 was targeted day and night by nearly 3,000 pilotless bombs, the deadly V1 and V2s. A total of 28,890 Londoners had been killed and another 50,000 injured. Many shops, businesses and domestic dwellings were eradicated – 100,000 houses had to be demolished. An estimated 1,650,000 sustained some sort of damage.1

The worst losses had been in the City of London. Out of the total of 460 acres of built-up land, 164 acres had been destroyed. Eighteen churches were beyond repair, including fourteen designed by Christopher Wren.2 Ten had been razed to the ground in a single night. Austin Friars, the Dutch church that dated from 1253, had been a light Gothic building and was now little more than ‘a rubbish heap’. St Giles Cripplegate, which Rose Macaulay wrote of – where Cromwell married and Milton was buried – was now a ruin. The statue of Milton outside the church had been completely blown off its pedestal. St Clement Danes in the Strand had been decimated. St Mary-le-Bow was reduced to a shell, her font destroyed and her famous bells irreparably cracked.

[The churches of London] had suffered a disgusting change, a metamorphosis at first stupefying. How could these dear interiors, panelled, symmetrically murky, personal, redolent of the eighteenth century, filled with ornaments and busts, urns, tablets, organ cases, carved swags, pulpits and galleries, pews, hassocks, and hymn books, have been turned into dead bonfires, enclosed by windowless and roofless lengths of wall, with pillars like rotten teeth thrusting up from heaps of ash?3

Even the colour of the city had changed, whether it was Victorian granite, modern concrete or even the ‘tweed-textured’ walls of earlier buildings; all had been scorched umber.

Seventeen of the city’s Company Halls – including the medieval Merchant Tailors’ Hall – were flattened; six others were badly damaged.4 The Inns of Court had suffered several times including the Middle Temple Hall, which had hosted the first production of Twelfth Night, Shakespeare’s bitter-sweet comedy of love and loss. The Guildhall, once the setting for major trials such as that of Lady Jane Grey and Thomas Cranmer, had been burned to the ground in 1940, just as it had been in the Great Fire of 1666.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9344)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5787)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5123)

Hitman by Howie Carr(5096)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4448)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4274)

Breaking Free by Rachel Jeffs(4218)

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann(4055)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3988)

American Kingpin by Nick Bilton(3887)

The Secret Barrister by The Secret Barrister(3711)

Molly's Game: From Hollywood's Elite to Wall Street's Billionaire Boys Club, My High-Stakes Adventure in the World of Underground Poker by Molly Bloom(3536)

Mysteries by Colin Wilson(3456)

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3386)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3138)

I'll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara(3082)

Rogue Trader by Leeson Nick(3046)

Bunk by Kevin Young(3001)